What's In A Label?

It couldn’t possibly be that hard, could it? A 4- by 6-inch piece of paper glued to an usually-shaped glass container. And apart from including a few basic items of information, you can design it any way you please.. A clean slate, if you will. So then why do some wine label designers totally miss the mark? Why are retailers and consumers alike perennially underwhelmed?

Let me start out by saying: Most labels are uninspired. Why?I think it’s because wine producers, and the marketing teams that work for them, don’t really know who they’re catering to. And even if they know exactly who they’re catering to, I don’t think they know exactly how to cater to them.

“Don’t judge a book by its cover.” Fair enough, but what about booze? How often have you selected a bottle of wine from a retailer based on your positive appraisal of the label, only to be disappointed with the glorified vinegar that you brought home? To our chagrin, the snazzy look of a label doesn’t guarantee a quality product in the bottle.

At its most fundamental, a wine label should communicate essentially what is contained inside the bottle, right? A simple wine should contain a simple label, and a fancy wine should contain a fancy label, right? But then again, what is fancy and what is simple? Is fancy always a positive descriptor, and is simple always negative? Hardly. Some of the best wines I’ve had have been simple beyond all belief because of the high quality of fruit, and some of the worst wines I’ve had have been so “fancy” with the addition of fake oak and the manipulation of alcohol levels, that I could barely drink them.

It is rare that a winemaker finds equal passion in designing a label as he or she does in coaxing delicious flavors out of fermented grapes. Though a viticulture or oenology degree from UC Davis will help you in the cellar, it’s not gonna serve you one bit when you go to market your product. And unfortunately, most marketing teams don’t have much experience in making wine, and suffer from a lack of knowledge about the product they’re promoting.

It’s understandable that producers are lost. With wine, you’ve got a weird hybrid of history and tradition meeting modernity and technology, and that nexus of two worlds is very evident than with wine labels. In a way, the French and the Italians have it easy because all they have to do is slap their family coat of arms or chateau on a cream-colored label and write their name in some cursive “classy” font, and they’re got it made, right? But even these centuries-old winemaking families are choosing to update their labels to appeal to a modern audience.

The discussion of traditional versus modern is an interesting one, I think. With your quintessential French or Italian label (please see breakdown below, with images!), producers of Bordeaux, Burgundy, Barolo, and Brunello (What is it with these “B’s”?) appeal to drinkers such as “old-timer” finance/banking/business types, as well as those obsessed with the lineage of the producer and the scores their wines receive from big-time publications. To these consumers, expensive wines must look expensive, and the more the label impresses their colleagues, the better.

Modern label designs are chosen by producers who wish to appeal to a contemporary audience, namely, those who are well-versed in the current state of the wine industry as well as younger drinkers. Many Old World producers have chosen to adopt modern-looking labels in an effort to demonstrate to their clientele that their product is relevant in today’s market, through replanting of fruit and investment in modern winemaking equipment and technology.

Crafting a label that appeals to a broad, oftentimes international, audience, can be a daunting task. While producers are, in theory, interested in their product being financially lucrative all around the world, drinkers from different countries gravitate toward different tastes, looks, and styles. American drinkers get frustrated when a label fails to contain the varietal or varietal blend (cuvee in French and uvaggio in Italian). America has the stereotype of being a varietal-driven people (“I love Mablec, hate Merlot,” or “Anything but Chardonnay,” are not uncommon comments). On the contrary, in Europe the region and producer are much more important--perhaps because most French people know that Chinon is always Cabernet Franc and Italians know that Barolo is made from Nebbiolo.

I think Old World producers would have more commercial success in the US market if they made sure to include the varietal breakdown on the bottle, even if it’s just on the back label. It’s understandable that the specific blend is not precisely known, not even to the producer. But some inclusion of what grapes you’re working with would help your consumers know what to expect.

In my opinion, the most important thing is that a label should stand out. One’s eye should be drawn to it from far away. If that’s the case, then why don’t label designers employ more time-honored marketing tricks to attract customers to their products?

Now onto the fun part. My brain always enjoys categorizing things, putting things into their proper place in my mind. Which is why I enjoyed this topic of discovering common wine label designs. Here’s what I came up with:

POPULAR TROPES

There are some popular tropes that have emerged in the past, say, 10 years.

- “Wild Wild West” Motif

One spinoff of this motif, or a subsection of it I should say, is the “outlaw” motif. Renegades, prisoners, delinquents, criminals, etc. are very popular subjects of wine labels. Who the hell knows. Maybe they’re marketed to millennial men who consider themselves “renegades” for drinking wine instead of Keystone Light like their frat bros from Syracuse or Dewars like their fathers. “I drink Shiraz, Bro. I’m a renegade.” While these labels are catchy now, it’s only a fad and it’s going to be over in a few years. And probably replaced by something equally as noxious.

2. The 5-Minute “Paint” Job

Guns. prisons, duels, etc. Very popular

4. Generic Malbec Look

Some motifs that interest me

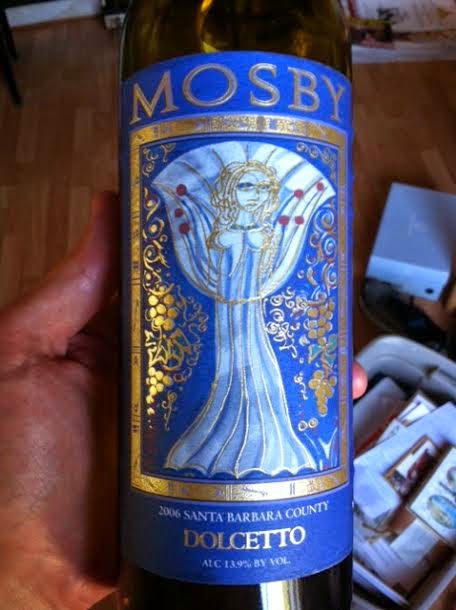

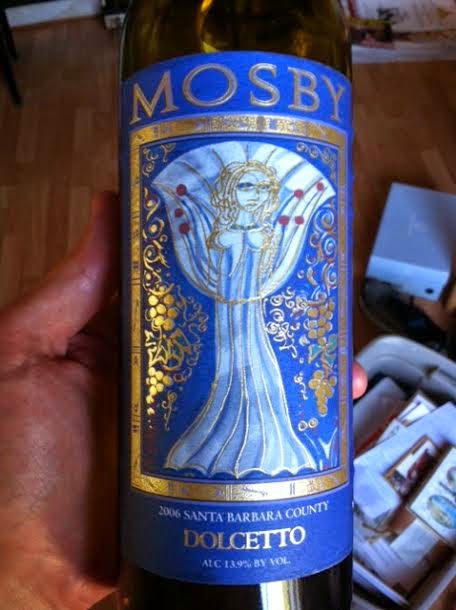

I love wine labels with lots of color (especially with gold trim. My how I love gold trim…) In particular there is a Cal-Italian producer in Santa Barbara County, California whose labels (and wine, of course) I have admired for a while. Bill Mosby is as artful with his wines as his local artist is with these labels.

I also really like floral or leafy designs

Wine Labels By Country In A Nutshell

Certain countries tend to adopt common themes. Here’s what I’ve gathered.

- South Africa: text-driven, with perhaps a clip-art image of some indigenous fowl animal

France: Pretty calligraphy with a gold-colored image of the family’s centuries-old chateau

- Italy: family crest with big, bold, capital letters. Red, black, gold, and ivory are only color options.

- USA: All over the place graphically, but American producers love using nature names like “Oaks, “Creek,” “Wood,” “Rock”, “Sea”, “Mountain”, and “Valley” on their labels. So, for example, if you wanted to start to bogus CA winery and sell lots of wine, I recommend calling your winery “Creek Rock” or “Mountain Valley” or “Oakwood” or something like that.

Unusual Finds from Obscure Regions

If you've never had a wine from Basilicata, Molise, Le Marche, or Lirguria, don't worry about it. These are probably the four Italian regions least known for wine production. And yet, I'm convinced that you can find good wine around every corner in this great country. So here's to good wine from weird regions.

Don't Get Them Confused!

Fiano vs. Friulano vs. Fiorano

Fiano: a high-quality white wine from Campania, which has DOCG status.

Friulano: a white grape from Friuli (surprise, surprise), which used to be called Tocai

Fiorano: a famed producer of a Grechetto and Viognier blend from Lazio

Cerasuolo vs. Cerasuolo

Cerasuolo di Vittoria: A blend of Nero D'Avola and Frappato from Sicily's only DOCG

Cerasuolo d'Abruzzo: a low-skin-contact red (almost rosato) wine made from Montepulciano

Moscato vs. Muscat vs. Moscatel vs. Muscadet

Moscato and Moscatel are the names given to Italian and Spanish expressions of the Muscat grape, respectively. Muscadet is white wine-growing area of the Loire Valley produced from the Melon de Bourgogne grape. While most muscat is sweet, Muscadet is definitely a dry wine.

Montebuena: Just Say No

I don't recommend the Montebuena Rioja, even though it's the go-to $10 Rioja for both Wine Spectator and any wine store that claims to know what they're talking about (*cough* Total Wine *cough*). There's none of the muscle of Tempranillo and none of the brightness of Grenache. In fact, there's really not much of anything. It falls flat on all accounts. Normally I'm fine with $10 wines that are only technically sound and fail to provide anything else. I mean, for any everyday price, what else can you expect? But there are so many other $10 and undewr Riojas virtually everywhere now, that it's just not necessarily to fall prey to the market hype of this bottle. I thought it was a waste of $10 the first time I tried it, but kept on hearing about it, so I made the foolish mistake of not trusting my intuition and I bought another bottle. Dumb, dumb, dumb. As they say, fool me once, shame on you, but fool me twice, shame on me. I can feel the anger boiling up in my body as I type.

Alcohol Content: A Personal Memoir

Friday, July 11, 2014 10:31 am

I recall very vividly sitting at the bar of my parents' restaurant when I was around 10 or 11 years old, waiting for them to be done with the day's tasks. A line of recently-delivered wine bottles was strewn on the bar, waiting to be put into inventory. I surveyed the bottles. I couldn't pronounce the words on the labels (as they were all in Italian), so I instead took note of the small "alcohol by volume" indication at the bottom of the bottles. Were they all the same? I wondered. I did some investigation. 12%. 12.5%. 12%. 12%. 12.5%. 12.5%. And I kept going. Finally I stumbled across a rare breed: 13% alcohol by volume. I was shocked. At the age of ten, I had no idea what it meant, but I knew it was different from the rest, so I was still shocked.

Fast forward to when I started drinking wine in California when I was *ahem* twenty-one years old. I was aghast to find bottles that came in at 13.5%, 14%, even 14.5%. These are not like the bottles I remember, I thought to myself naively. And lo and behold, these more alcoholic bottles weren't met with as much of my pleasure as were the more simple, lighter red wines that I had grown accustomed to while living in Bologna.

Mind you, my first exposure to alcohol content was from Italian wines in the mid-1990s. The geography and climate of California is, despite what some viticulturists might claim, quite different from Italy, and, anyway, wines are being made with higher alcohol contents now to appeal to a changing consumer palate. So this raises the question: Does my preference for lower-alcohol wines stem from an objective estimation, or am I still a slave to "what I grew up with"? I might never know. But in the meantime, pass me the Dolcetto....

How to make the perfect Espresso Martini

Tuesday, July 8, 2014 6:44pm

Mmmm, Espresso Martinis. Just

saying it conjures up images of….espresso…and martinis…..No, but seriously,

these are the perfect late-night, after-dinner indulgence. Your mom used to

serve coffee when she wanted guests to leave. But you? You’ll serve espresso

martinis.

These are like White Russians

on steroids. Everything is one-upped. Limit yourself to one a night, unless you’re

itching to develop Type II Diabetes. I don’t recommend substituting this for

your morning cup of Joe.

There are four components to

this martini:

The Alcohol

Vodka only. Do not experiment with other alcohols. It

won’t work, and I will disown you. Unflavored vodka is fine, but you can

also experiment with a host of flavored vodkas, like Smirnoff Vanilla, Pinnacle

Whipped Cream or Three Olives Triple Shot Espresso or Chocolate. Just be

careful, because these flavored liquors will add sugar to the concoction, which

may or may not be desired.

The Liqueur

There are so many that work

great. I really love Frangelico and Kahlua, but Bailey’s and Godiva White

Chocolate are also nice. I’ve also considered using Crème de Cacao or

Disaronno, but I can’t speak on those with experience. Anything that adds depth

of flavor is acceptable to me!

The Coffee

Crucial that you pull your

own fresh espresso shots. Iced coffee will certainly not do the trick. Nor will

Kahlua alone, as it provides too much sweetness and not enough fresh coffee

flavor. Don’t even try instant coffee—that shit is disgusting. Again, regular

coffee beans are fine, but there are a ton of flavored coffees that work great:

vanilla, hazelnut, dulce de leche, macadamia nut—the list goes on. Go to the

nearest TJ Maxx,

Crucial that you pull your

own fresh espresso shots. Iced coffee will certainly not do the trick. Nor will

Kahlua alone, as it provides too much sweetness and not enough fresh coffee

flavor. Don’t even try instant coffee—that shit is disgusting. Again, regular

coffee beans are fine, but there are a ton of flavored coffees that work great:

vanilla, hazelnut, dulce de leche, macadamia nut—the list goes on. Go to the

nearest TJ Maxx,

The Cream

Heavy whipping cream is best.

Make sure it’s really cold before you mix it in with the martini. Half-and-half

also works ok, but it has the potential to curdle if not mixed properly. I’d

avoid milk, as it will create too watery of a consistency. If you’re on a

budget (or just White Trash, or lactose-intolerant), using nondairy creamy

works fine. There are many different flavors that work well.

The Ingredients

1 oz vanilla vodka

1 oz Frangelico

2 oz fresh-brewed espresso

1/3 cup heavy whipping cream

The Process

It’s ideal to have your vodka

as cold as possible. Put it in the freezer the night before mixing (I always schedule

my espresso martinis 24 hours in advance so that this can happen).

1. Chill your martini glass

in the freezer. No, seriously. Go do it now.

2. Pull your espresso

shot(s). 1-2 shots per martini, depending on the desired coffee flavor strength

3. Instantly mix your

espresso with your cream source. Do not allow your espresso to cool by itself,

as it will turn bitter

4. Put your espresso and

cream mixture in the freezer for 10-20 minutes.

5. Shave chocolate onto a

plate

6. Get your martini glass and

espresso mixture from the freezer and combine with vodka and liquor in a

martini shaker with some ice.

6. Wet the rim of your

martini glass and dip in chocolate

7. Pour contents into martini

glass, and enjoy

The drink you are about to

enjoy is sweet, intense, creamy, bitter, nutty, and perfectly balanced.

Italy is home to somewhere between 350 and 500 different grape varietals. Twenty years ago, "Italian wine" was synonymous with "cheap Chianti" to most American drinkers. Images of red-and-white checkered tablecloths and thick spaghetti with meatballs came to mind. Things are very different now, as many less-recognized Italian varietals provide just as high-quality wines as the Chiantis that drinkers of the '90s were accustomed to, at a much more desirable price-quality-ratio. The following is a list of obscure varietals that I've experimented with over the past few years. All of these wines are included in the review section. Lo and beyond, all these wines are from different, less-known Italian regions, as well.

Petit Rouge: hails from the Northwest region of Valle D'Aosta. Yea, don't feel bad if you've never heard of it. I lived in Italy for a year and had no idea it existed. You'll more than likely see bottles labelled "Chambave" as this is subregion to which the Petit Rouge varietal normally offers its services.

Cesanese: light red wine from Lazio. Truth be told, this is the region's only red grape of note, and it's a small note at that. I drank the Marco Carpineti Tufaliccio and could not distinguish it among the other light, tart, young red wines that I drank over that three-month period. With all those epic Hollywood blockbusters depicting Roman emperors drinking wine, you would think that the Lazio region would have discovered a more well-known grape to grow themselves, no?

Schiava: from the Alto-Adige region (also known as Sudtirol). You might be more familiar with Lagrein and Teroldego, two very similar red grapes that also come from this region. The bottles will almost never say Schiava, but will more than likely read "Klausner" or "St. Magdalener", which are two of the more visible appellations of the grape.

Gaglioppo: red wine from Calabria. You'll more than likely see the label say "Ciro", but that is not the grape name. These wines are light and very drinkable and bear no resemblance to other Southern Italian wines like Aglianico or Nero D'Avola.

Monica: red grape variety from Sardegna not to be confused with Cannonau. I can't really describe the qualities of this grape, as the bottle I drank was not indicative of it, I don't think.

The Cal-Italian Movement

The scope of the Cal-Italian movement is to not only offer American drinkers domestically-grown Italian varietals, but to grow these varietals in the Old World Italian style. Italy’s almost limitless varietals require equally limitless growing conditions and climates, so to attempt to recreate these wines all within the context of California’s arguably less diverse Mediterranean climate is a daunting task. There are many efforts out there, and not all of them are successful. My goal here is to highlight three wineries that I feel have excellent above others in this mission.

The first winery I’ll highlight is the winery I first truly fell in love with: Mosby winery in Buellton (a city more well-known for pea soup than wine.) Bill Mosby is truly a visionary in the world of the Cal-Italian movement. Bill purchased land near the Santa Ynez River just outside the Santa Rita Hills appellation in 1963 and planted vines in 1971, almost twenty years before the Cal-Italian movement really took off (cal-italia.org). What prompted him to make such a bold and counter-wine-cultural gesture? Was it merely blind faith in the potential for these Italian varietals to thrive in Central Coast soil? Today Bill offers a slew of interesting and well-nurtured wines, many of which are rare finds.

The star of Bill’s lineup, in my opinion, is his La Seduzione, an interpretation of the Lagrein grape. Lagrein is a grape indigenous to the Trentino-Alto Adige region of Northern Italy. I’ve tried a few Lagreins from Italy, and I’ve enjoyed most of them. In general, they are simple, identifiable wines with concentrated flavors that are intended to be drunk fairly young. I’ve also had an excellent California-grown Lagrein from Alapay winery in Avila Beach. Apart from those two, I can’t think of any other Lagreins grown in California.

The star of Bill’s lineup, in my opinion, is his La Seduzione, an interpretation of the Lagrein grape. Lagrein is a grape indigenous to the Trentino-Alto Adige region of Northern Italy. I’ve tried a few Lagreins from Italy, and I’ve enjoyed most of them. In general, they are simple, identifiable wines with concentrated flavors that are intended to be drunk fairly young. I’ve also had an excellent California-grown Lagrein from Alapay winery in Avila Beach. Apart from those two, I can’t think of any other Lagreins grown in California.

La Seduzione (“Seduction”) is a medium-bodied wine with a deep velvet hue in the glass, darker than garnet and with more shades of brown. It possesses a hearty, rustic taste uncharacteristic of a California wine. This wine is definitely more of a sensation than a taste. I experienced an enjoyable burn that hits almost all parts of the tongue and the roof of the mouth. I’ve never encountered a mouthfeel like this wine. A languishing finish that continues to develop well after the sip is over. This is a fascinating wine.

A close second to the Seduzione is Mosby’s Sagrantino. Sagrantino is Umbria’s claim-to-fame varietal, and Sagrantino di Montefalco wines are big and expensive and just as collectible as Chianti and Barolo. I drink a bottle of this every year or so, and I’m never disappointed. While this wine is more elegant and less intense than its Italian counterpoints, it’s still a hefty wine and should be decanted. If allowed to breathe, it will reward you with irresistible notes of potpourri and fresh rose petals (Truly a bouquet, if you know what I mean). On the palate I was struck by the gorgeous fruit presence, most notably stewed cherries. This fruit is honest and natural. Also substantial notes of raw red meat. This is a wine that you sip slowly and relish. I crack open this bottle when I want a real treat. One thing about the most recent bottle (from last night) was that it didn’t seem to hold up well. I enjoyed the bottle much more during the first hour, after which it turned musky and tart. Nothing off-putting, though. I still enjoyed the wine a great deal and will continue to come back to it. One of the few Sagrantinos grown in California, and I would be hard-pressed to find one that exceeds it in quality.

I also really enjoy Mosby's interpretation of Dolcetto. It's much more fruit-forward than any Italian Dolcetto you'll find, but that's ok in this case. Again, really excellent purity of fruit. It compares to, say, Palmina or Jacuzzi, but not as candy-like as the others. Don't tell anyone this, but the winery sells it for $28, and I can get it at my local CVS (I know, right) for $15. At least, last time I checked....It went really well with pan-seared salmon when I made it!

I also really enjoy Mosby's interpretation of Dolcetto. It's much more fruit-forward than any Italian Dolcetto you'll find, but that's ok in this case. Again, really excellent purity of fruit. It compares to, say, Palmina or Jacuzzi, but not as candy-like as the others. Don't tell anyone this, but the winery sells it for $28, and I can get it at my local CVS (I know, right) for $15. At least, last time I checked....It went really well with pan-seared salmon when I made it!

Mosby’s economical vino da tavola, Lucca, is an excellent bargain for $10. Fruit-forward and bright, this wine is Zanfandel-based and definitely closer to the juicy California-styled Zins than the dry, earthy Primitivos of Puglia. Mosby sells this for $14 but I can get it at the local CVS for $10.

One of Mosby’s wines that I was disappointed with was his Sangiovese. I’m a freak for Sangiovese so had high expectations for this bottle. But the acid presence (which in Sangiovese must be vigilantly monitored) was too overwhelming to even detect any of the other components. I thought that perhaps this flaw was particular to the first bottle I tried, but my initial suspicion was confirmed with the second bottle.

Stay tuned for my reviews of my two other favorite Cal-Italian wineries, Toccata and Jacuzzi.

The Drunk Dago's 4th of July Sonoma Wine Tasting Extravaganza!

I just returned home from a four-day road trip to Sonoma Valley Wine Country, and I have a lot to share about the state of the wine industry up there! Sharing the duties of driving and navigating was my "wife" Heather, who past this point will be referred to by her wine pseudonym, The Sober Swede. Along the way we were fortunate enough to spend some time with and accept the gracious hospitality of my two aunts, Rita and Regina, who live in Arroyo Grande and downtown Sonoma, respectively.

Because this was The Sober Swede's first time experiencing wine tasting in that area (we're more familiar with Central Coast wine, due to proximity), I "allowed" her to choose a few wineries, and I selected some myself. Due to the nature of this blog, of course, I gravitated toward wineries that featured mostly Italian varietals, whether or not these wineries actually called themselves "Cal-Italian".

A short drive up the 101 had us stopping in beautiful Avila Beach. It was a clear, modest evening and a throng of people were on the boardwalk enjoying live music, food stands, and each others’ company. Back to work for us, though, as we were sampling some interesting wines at Alapay. More on that and reviews from the rest of our trip later…..

Now in Arroyo Grande, Aunt Rita (pictured above, sunning herself) and Uncle Bill accompanied us to Edna Valley, a beautiful campus and tasting room that unfortunately didn't equate with good wine. We sampled a white Rhone blend ("V" for 5 varietals) that reminded us of raw garlic. The Reserve Chardonney was heavy on vanilla, but certainly not offensive, which is a compliment seeing as I typically avoid the stuff. The 2008 Petit Verdot had a confused flavor profile and no mid-palate, but as far as I'm concerned this is par for the course for this third-tier Bordeaux varietal. The 2008 V Red Blend was spicy. We tried the 2007 Reserve Syrah that was heavy on vanilla. We enjoyed the Sweet Edna, a refreshingly sweet Moscato.

Off to Saucelito Canyon, which, other than a snarky, jaded pourer, was uneventful and bland. A laundry list of Zinfandels that were way too alcoholic for their own good.

Our next stop was Qupe, a winery in Los Olivos known for their Syrah and Rhone blend. In fact, they are one of the original members of The Rhone Rangers, a group of winemakers primarily based in the Central Coast regions of Santa Ynez, San Luis Obispo, Santa Maria, and Paso Robles who seek to glorify the merits of tradition Rhone Valley varietals, where Syrah reigns supreme. Heather wanted to stop by and say hello to what could possibly be her long lost cousins, as she shares a last name with founder and winemaker Robert Lindquist.

We started with the Viognier, a traditional Rhone white known for being particularly aromatic. This varietal was new to me. On the nose and palate quite similar to Savignon Blanc, which surprised me. Refreshing and crisp. Some heat going down. We tried a Roussane (another Rhone white) that had a very nutty feel and taste to it. I was reminded of cashews. Ethan, Robert's son, who poured for us, mentioned it would age well. We moved on to their Tempranillo, a varietal near and dear to my heart. I was impressed with the austere, bone-dry, Old World quality of this wine, which is almost never found in California, and has a reputation of being lackluster when it is found. The wine was extremely savory (entirely fermented), and reminded us of a smoky rub for meat (tri-tip or ribs) rather than something fruit-based. I found this welcoming. Also, curiously light for a Tempranillo. I'd buy a bottle. Sort of bummed I didn't. The Grenache was characteristically spicy and well-balanced (another varietal I go crazy for if I don't watch myself). We sampled three Syrahs, the Central Coast Syrah (which you can buy at many retails stores, including Costco, for about $15), the Los Olivos Syrah, and the Bien Nacido Vineyard Syrah, the last of which being the only one I was impressed with. I prefer my Syrahs spicy, heavy, and loaded with vanilla and cream, and this delivered modestly well. Quite well-balanced, but I still prefer Bridlewood Dusty Trails for the price point.

Our first stop, and this was truly spontaneous, found us at Mosby winery in Buellton, just off the 101 Santa Rosa exit about forty-five minutes North of Santa Barbara. The Sober Swede is a wine member here and got me fixed on the wine too when we tried Bill Mosby's Sagrantino three years ago (As far as I know he has the distinction of being the only California vintner to grow this varietal). I respect what Bill Mosby does: he seeks the purity of expression of only grape varietals indigenous to Italy. I like many of his wines, although I'm not swayed by his complete offerings.

In the tasting room we sampled (for free....yay) the 2008 Dolcetto, which they sell there for $24 but which I found at my local CVS (in Camarillo of all places!) for a killer $15. This wine was better than I recalled, more elegant and balanced than when I drank it a year ago. Next was the Sangiovese, which showed itself to be just as acidic, one-note, off-balance, and puckery as when I first tried it about nine months ago. Next was the 2005 La Seduzione Lagrein. I was blown away by this wine's otherworldly mouthfeel when I drank it about six months ago, especially when paired with mushroom and parmesean risotto. I didn't get as much action in the mouth this time, which led me to confirm it must be paired. As a special treat we were offered their dry orange Moscato, which I thought was ok (I prefer sweet Moscato) and Sophia, the raspberry liquer, which is always worth dying for!

This Easter we cracked open two wines that we thought would pair well with the leg of lamb I prepared: the first was the 2007 Morgan Cotes du Crow's Syrah-Grenache blend from Monterey. The second was the 2009 Alapay Lagrein from Avila Beach in San Luis Obispo County.

I was excited about the Morgan for a few reasons. I had been itching to try another California Rhone blend after enjoying a series of very good Syrahs or Syrah blends (the 2006 Bridlewood "Dusty Trails" Syrah from Santa Ynez, a $32 bottle of wine, and the $12 2007 Pantheon Syrah-based Rhone blend also from Santa Ynez.....hmm I'm detecting a pattern.) When choosing California wines (which is honestly a rare occasion), I've noticed my palate shifting away from Cabernet and Merlot, and I find many Zinfandels to be one-dimensional. So recently Syrah has been my California varietal of choice.

I stumbled across some website saying that the Morgan was the perfect bottle to pair with Easter dinner. This, of course, was after I had bought it. What luck.

Now I don't have enough experience to tell you what region of California produces the most promising Syrah, and my hunch is that even the most avid Syrah drinker would find that question difficult to answer. So Monterey County was an experiment, to say the least. Monterey County is certainly a lesser-known California Appellation, and as far as I know experiences milder climates more conducive to cold-weather grapes. Well, Syrah isn't a cold-weather grape, but Grenache can be, depending on the desired style of the wine. And Syrah is truly a chameleon, contorting to whatever style the winemaker chooses. And I imagine the climate of Monterey is more akin to that of the Rhone Valley than, say, Napa or Sonoma.

This wine was, in fact, quite reserved, and I appreciated that. I've had my fair share of fruit-bomb California Syrahs that offer little more than "Smuckers jam"-like flavor profiles and absurdly high alcohol contents worthy of competing with port. This is most common in warm-climate locations such as parts of Napa Valley (or some more sun-drenched mesoclimates of Paso Robles) where the Syrah grape can grow to be extremely juicy, and where vintners do very little to limit yield or harvest the grape early.

Some really lovely lush fruit on the nose that unfortunately didn't translate so well onto the palate. The Syrah comes through very nicely but I felt like the Grenache was a lame duck pairing. Mediocre Grenache grapes? Watery grapes? Also, no spice whatsoever, which is atypical of this classic pairing, and which was something I was looking forward to. Worst of all, a very bitter finish that made me squint and pucker. There's nothing worse than ending poorly. Overall, I was disappointed in this effort.

For fun, my brother-in-law, his wife, and I did a blind pairing of this "variable" wine against the $6 2008 Valreas Cuvee Prestige Cote du Rhone Village, which functioned as a sort of cheap foreign "control" wine. While we all agreed the Morgan was more interesting, it wasn't a hands-down winner. And considering that at least $1.50 of the French wine goes to shipping and import taxes, I was almost embarrassed for the Morgan!

My family noted what a perfect pairing to the lamb this made. The recipe I'll post later....

What makes a good bottle of wine?

What to look for in determining the quality of a bottle of wine.

1. Fidelity to the Grape and Land

This is known as typicity. Look for pure expression of the varietal without other components interfering. These can include high alcohol levels, over-oaking, or an over-abundance of residual sugar that leads to an overly-sweet wine. Ask yourself, Does this Cabernet taste like a Cabernet? Novice winemakers will first seek to create a pleasing wine before caring whether or not the wine represents the grape it's made from. Good winemakers know what to do in the vineyard and the cellar to bring out the redeeming qualities of a particular grape while side-stepping the grape's potential pitfalls. For example, Pinot Noir has the remarkable ability of expressing the personality of the terrain in which it was planted, but can be highly acidic if not cared for properly. I've tasted so many Pinot Noirs that were decent wines but I would have never guessed they were from that varietal. And yet I can respect a very entry level Aglianico, for example, that is unabashedly a member of this varietal group, because the vintner knows his subject.

A good wine is also clearly a product of its nationalistic origins. Wines from Italy have a particular flavor to them, based on the soil, climate, and topography of the land. This is the same for wines from France, Spain, or any other wine-producing area. This is the basis for the French term terroir.

2. Balance

A wine is of quality if its levels of fruit, alcohol, tannin, and acid are all harmonious. It’s a good sign when you don’t notice any of these during your first few sips. While with some varietals acid levels will be inherently high, and it's a fact your palate must acclamate to, and certain grapes produces wines that are more tannic than others, a good winemaking process will equalize these factors.Young wines from the Nebbiolo grape can be offensively tannic, which is why many of Piedmont's top producers will hold their bottles from the public for a good four or five years (with Barolo and Barbaresco this is legally obligatory). A lack of one of these elements is also a flaw in wine. A wine with low tannins is said to have no backbone, and a wine that doesn't bring out fruit is said to be inaccessible.

A concept very similar to balance but certainly independent from it is structure. Structure goes beyond the harmony of chemical parts and is often difficult to describe. Structured wines are not watery, flabby, or confused. Their flavor profiles are clear, and they are confident in their own identities. If a wine reminds you too much of something you've already tasted (perhaps even a wine completely unrelated!), then it can't have structure. The tannic acid in red wine makes it very appealing to drinkers--especially when paired with food--because it provides the wine with great structure.

3. Complexity

We're talking about secondary and tertiary characteristics. This is essentially the mid-palate. Unless you're a sorority chick from USC, you know that wine should taste and smell like more than just alcohol and grapes (Thanks, Laura.) Wine tasting gets very interesting when you start to sense lavender and rose petals on the nose, and taste hints of tar or tobacco. The chemical compounds of fermenting grapes are particularly volatile, which means that they can very easily change to mimic the characteristics of other naturally-occuring items, such as fruit, botanical products, or even livestock. This makes wine interesting. Quality wines are made in a fashion to reveal these secondary characteristics. Here, one must be particularly sensitive to palate preferences. There's a particular Spanish Garnacha that I love for its overhwhelming notes of pomegranate. While I am tempted to rate this wine high for its price point, I must remember that my palate probably responds better to the taste of pomegranate than most palates.

Complexity can also refer to the sophisticated power struggle that the difference components of a wine undergo. At first tasting, the acid is king, as the palate adjusts to this affront. Then, the fruit comes through in the attack, but diminishes after time. Upon swirling, the tannins take control, as numbing of the tongue, mouth, and walls of the cheek occur. Alcohol reveals itself in the swallowing, as a highly alcoholic wine will mimic the sensations of taking a shot of hard liquor, although not as intense. In good wines, these elements will overlap and return at different times, making the wine tasting experience multi-layered.

4. Drinkability

This refers to the ease with which wine is consumed. Here, lighter wines have an advantage over heavier wines because it’s more likely that a heavier wine will have off-putting qualities. Do not confuse “drinkable” for “palatable”. “Palatable”, strictly speaking, means “sufficiently agreeable in flavor to be drunk.” Basically, you say a wine is palatable if you’re not choking. Some wines are not palatable. Either it’s corked, it was stored improperly, or the winemaker had absolutely no idea what he was doing and the wine is essentially fermented vinegar. “Drinkable” means that it’s easy to drink. Drinking wine shouldn’t be hard work. If you know a bottle of wine is of quality, but requires too much cerebral effort on your part, it means it’s unapproachable, and that’s a flaw in its own right.

5. Character

The wine may be technically sound and attractive on the palate, but it must be distinguished from other wines of its type. Does it offer something special? Will you remember the wine? Does the wine expand your knowledge of this style? Have you had a wine of the same genre and price point that you preferred over this one? Here, specificity is key. Syrahs are known to be spicy, but is the spiciness in this wine generic, or do you sense nutmeg and curry? A Sangiovese may taste like strawberries, but does this Sangiovese remind you of fresh-cute strawberries candied in brown sugar?

6. Finish

A wine's finish, the lingering of flavor and sensation in the mouth after swallowing, is not only an enjoyabe experience, but also an indicator of a wine's aging potential, and hence its quality. A finish should never be surprising or offensive, but rather should leave the palate with a warm, comforting feeling, and also a higher-than-carnal desire to drink more. Here, wine is often compared to other grand works of art. One doesn't forget a viewing of the Sistene Chapel, for example. Thoughts continue to return to that experience, as if time stood still. This is in fact quite possible with a fine bottle of wine. A wine transcends the mere sensory experience and begins to tap into our emotional core.

How To Drink Wine

The following is a step-by-step guide to understanding and enjoying any bottle of wine.

STEP 1 Don’t brush your teeth beforehand! Do you want peppermint-tasting Chianti? Also, no gum.

STEP 2 Don’t taste wine on an empty stomach. Your taste buds will trick you into believing the wine is good simply because you want something in your body. You should eat beforehand. Simple carbs or foods rich in fat are ok. Nothing spicy or unusually flavorful.

STEP 3 Choose proper stemware. Riedels are high-quality glasses and they’re not too expensive. It has been scientifically proven that good stemware improves the flavor of wine. Make sure they’re clean and polished.

STEP 4 Allow the wine to breathe. This goes for all types of wine. For young, simple wines, 30 minutes is ok. For older, more complex wines, anywhere from 1 to 3 hours is necessary. Breathing allows oxygen to meet with the wine, which is vital since the wine’s flavors have been cramped in a tiny bottle for anywhere from 1 to God-knows how many years.

STEP 5 Decant the wine. This is the process of putting the wine in a decanter. Essentially the same as breathing but opens the wine up even more. If you decant you don’t need to let the wine breathe as much. Also, decanting allows you to analyze the color and bouquet of the wine better than when it’s just in the glass.

STEP 6 Smell the wine. Verbalize any and all thoughts that come to your mind. This is a brainstorming activity. Therefore, all ideas are acceptable. If it smells like rubbing alcohol, you’re probably right.

STEP 7 If you’re serious, do a blind tasting. This is where you sample the wine without any prior knowledge of the label, ie the type of wine, year, winery, etc. This can be very fun! Obviously you would need someone else to have bought the wine. Write down your initial comments. If you want, try to guess varietal, region, year, style. Ie “This must be a California Cabernet. Lots of oak. Perhaps blended with something softer. I’m guessing Napa. It’s aged, so we’ll say 2006.”

STEP 8 Taste the wine. Take a healthy sip, let it linger in your mouth for a few seconds, gargle if you’re so inclined, and the swallow. Be aware of the tastes and sensations that take place the very second your sample it (the attack), while you gargle (the mid-palate), and after you swallow (the finish). Do you get a lot of sugar? Alcohol? Tartness? Acidity? Burn? Warmth? Smoothness? These are all ok to some degree. If you notice all of these simultaneously in a harmonious manner, then you’ve got a good bottle of wine on your hands! If one of them overpowers the others, you’ve got a wine that needs some work. Don’t minimize the importance of your gut instincts—go with them.

Step 9 Pair the wine with food. If you’re not eating a meal, foods such as chocolate, cheese, or cured meats are all appropriate. Perhaps something spicy. See how it complements a variety of foods. Characteristics of the wine will appear that before were hidden. “This curry brings out a lovely spicy component to the Syrah.”

Step 10 Check to see how the wines fares over time. Are your thoughts after the first glass the same? Remember, you are drinking something that is unusually acidic, bitter, and tart. Your taste buds need time to re-focus. Do you notice imperfections now that you overlooked at the first sip? Often times wines will prove to be too tart to truly enjoy, when at the beginning the tartness was a refreshing characteristic

Step 11 Let the wine stay out overnight. Cork it and try it again the next day. Have the flavors changed? Poor wine will be almost intolerable a day later, but good wine will keep its form.

No comments:

Post a Comment